How best to structure your organization

Businesses need structure in order to function and grow.

A good organizational structure answers three questions:

- How are responsibilities divided?

- Who is working together?

- Who reports to who?

Without such structure, it would be unclear to people what they’re responsible for, who they manage, and who they report to. Assuming you would want to avoid such chaos, it’s important to have an understanding of the different organizational structures and how you best organize your own organization.

The easiest way to get an understanding of organizational structures is to first look at the early days of almost every company.

The early days of a business

Most organizations are started by a handful of people, the founders. When the company is just 2 or 3 people, the founders have to cover a wide array of responsibilities. After all, also a startup needs to build a product or service (product and/or engineering), acquire leads (marketing), convert them to customers (sales), and keep them as happy customers (customer success). And then I’m not even talking yet about finance, recruiting, office space, and all the other things that need to be taken care of.

For founders, whether or not you have experience in these areas doesn’t matter. Never done sales? With no budget to hire someone, one of the founders will have to convince prospects to buy your product or service.

The first hires

When the business starts getting traction, the founders are constantly juggling to cover all the areas of their business. The pressure will increase to start hiring people.

The first hires will all report to either the CEO or the founders, which keeps the organizational structure simple and flat.

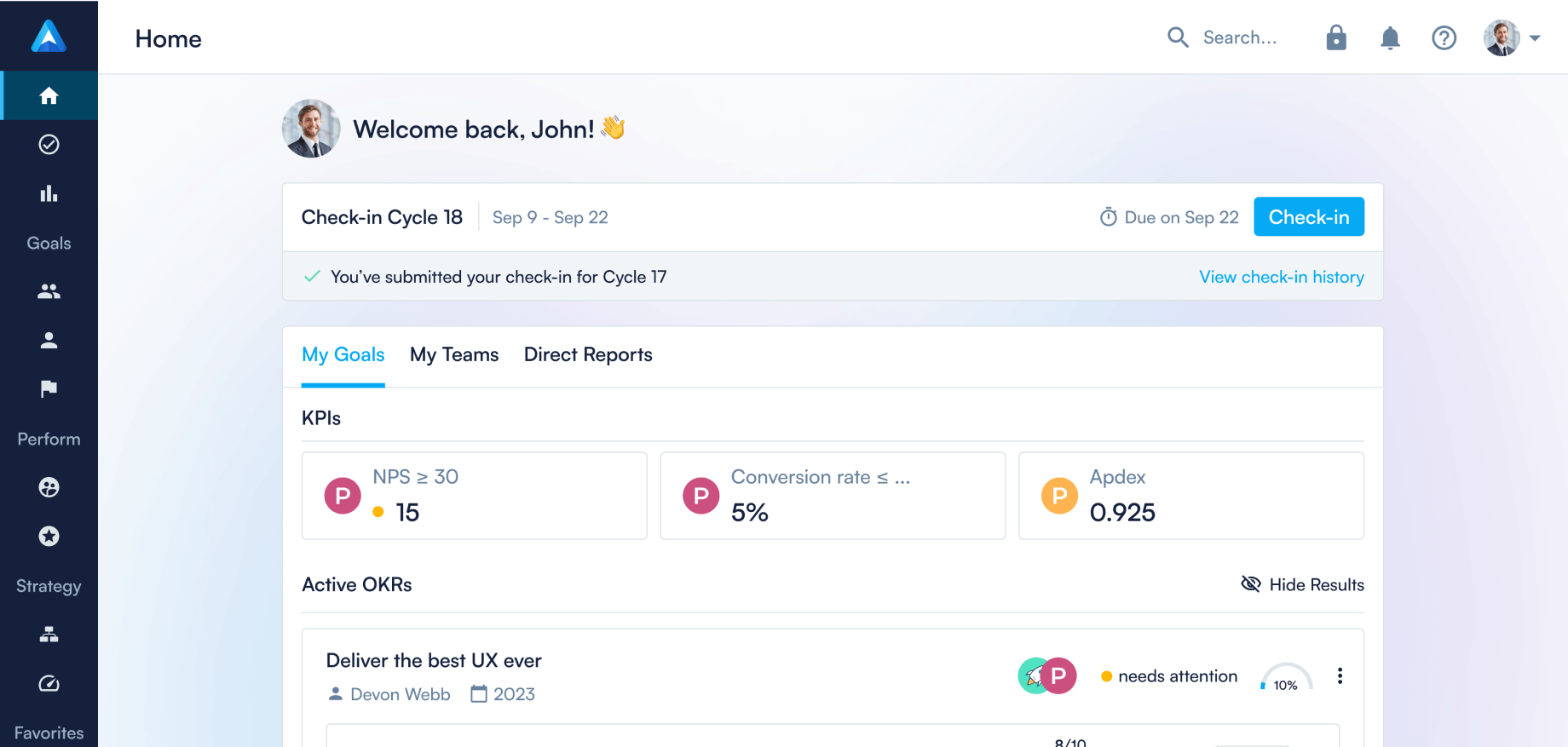

Each hire will have his or her own responsibilities. Ideally these are written down in a job description and include clear measures of success: KPIs.

The first hires typically cover different functional areas (e.g. product, engineering, marketing, sales, or support). Within these functional areas certain processes have already been built up by the founders. When these processes are successful, they become business as usual, and now these processes need to be executed by someone else. That person can then take it to the next level and the founders can focus on the next thing.

Example: If the founders managed to build up a steady stream of leads, and worked out a sales pitch or sales process that resulted in a decent lead-to-customer conversion rate, it’s time to bring in a salesperson who can take over this process (and possibly bring it to the next level). If the business fails to attract a good salesperson to take this over, it will mean one of the founders will have to continue to do sales, which will likely limit or harm the future growth of the company.

When it’s time to add structure

At a certain point, it will be time to add structure to the organization. The question is: when?

According to research, there is no universal optimal team size. However, there are two concepts that can help you figure out when it’s time to (re)structure your business: span of control and the two-pizza teams rule.

Span of control

The ratio of manager to direct reports is called the span of control. As a simple rule of thumb, a manager can have max 7 direct reports.

However, the actual number of direct reports a manager can have depends greatly on the teaching and assistance a direct report requires. This concept is called the span of managerial responsibility and was first introduced by Peter Drucker (the inventor of Management by Objectives, a precursor of OKR) in his book The Practice of Management.

Tomasz Tunguz, a former Product Manager at Google, researched this topic at Google and found that the average span of control was 1:7, but that there was great variance. Some senior teams had ratios of 1:20 or higher, while junior or innovative teams had ratios as low as 1:2. This research proves the span of managerial responsibility does indeed define how large a manager’s span of control can be.

To keep it simple, let’s follow the rule of thumb which dictates that as soon as a founder has more than 7 direct reports, it’s time to add structure and start organizing some of those people into (sub)groups.

Two pizza teams

Another way to look at the maximum size of teams is Jeff Bezos’ “two pizza teams” rule. Jeff Bezos says that if you can’t feed a team with two pizzas, it’s too large. That limits a team to 5 or 7 people (assuming we’re talking about American-sized pizzas ). The simple reason for this is that smaller teams communicate better, are more focused, and more effective.

3 common ways to get organized

There are three common ways that organizations use to structure themselves. I’ll first discuss the two extremes (functional and cross-functional), but most organizations use a hybrid form (option 3).

As a reminder, these organizational structures define:

- What are you responsible for?

- Who are you working with (i.e. which teams are you a member of)?

- Who do you report to and who reports to you?

1. Functional

The functional structure divides the company based on functional area or competency. For example, all the marketing people are together in one marketing team, which is then usually the only team they’re a member of. They’re sitting together in the same room.

When the team is still only 2 people, they often report to the Founder/CEO. When the team has 3+ people, they probably report to a Head of Marketing. The Head of Marketing is ultimately responsible for realizing the mission of the Marketing team.

When the Marketing team continues to grow, subgroups may start forming within the Marketing team (e.g. a Content and/or SEM team).

Most traditional organizations are structured this way, because a functional structure is very natural to us. Where Marketing is often about one-to-many relationships, Sales is usually about one-to-one relationships. Sales is often focused on “wins” and short term relationships, whereas Customer Success is more about nurturing long term relationships. Someone who loves Marketing may not succeed in Sales and Customer Success, and the other way around.

Pros

The main benefit of a functional structure is that it’s easy to understand. The responsibilities are clear and that limits confusion. Since the members of such teams have similar skills and interests, this structure enables individuals to easily learn from, and help each other.

Cons

The downside is that it can create silos, and it may be hard to facilitate good communication between different teams. That’s usually not a problem in commercial teams like Marketing, Sales, and Customer Success, where everyone is responsible for specific parts of the customer journey. But it often is a problem for tech teams like Product and Engineering, where most of the challenges require people from different functions to seamlessly work together.

2. Cross-functional

A cross-functional system (also called a squad or pod system) distributes the workload based on things like problems or challenges that the organization has, or certain values that need to be delivered to the customer.

Such cross-functional teams can also form around things like products or countries. A gaming company that markets several games may decide to have different people work exclusively on each game. Also an e-commerce company could decide to have country teams, so that each country has a dedicated marketer and salesperson that deeply understand the culture of that country.

A squad typically consists of around 5 to 7 people, with max 2 or 3 people from the same functional area (e.g. a product person, two engineers, a designer and a customer support representative). The squad typically is the only team they’re a member of (although at Spotify people from a specific functional area also group themselves in so-called ‘tribes’. Within these tribes, members can then share learnings and get help from people with similar skills and interests).

Members of a squad share an office, and they report to the head of that squad. The head of the squad is ultimately responsible for realizing the mission of that squad.

When the organization continues to grow, additional squads start to form.

Pros

Organizations that use this structure recognize that it requires people from different functional areas to solve certain problems or to deliver certain values—which is also its main benefit. This structure helps break through (functional) silos and the structure may be better equipped to solve certain challenges the organization faces.

Cons

The downside is that it sometimes is hard to understand. Less people are familiar with this system which is why it could be confusing. If implemented in an extreme form, another downside is that marketers are siloed from other marketers, so it’s harder for them to seek help and learn from peers.

3. Hybrid

According to our research, most organizations use some sort of hybrid of the two.

The most obvious examples are organizations that work a lot with project teams. Project teams are often cross-functional and usually exist next to a functional structure. Such projects teams are temporary, however, and our research has pointed out that most organizations that work with a hybrid structure have permanent cross-functional teams.

Such organizations are typically matrix organizations or tech companies:

Pros

The hybrid form is flexible and, if used well, can combine the best of both worlds.

Cons

It might be confusing. It is especially confusing when using a matrix structure where people have more than one line manager. Who do people listen to when there are conflicting priorities?

The right structure for your organization

You might be familiar with the concept structure follows strategy. However, strategy can and will change, which may not always justify a complete reorganization. Therefore, a better, slightly different approach to orient structure towards could be: structure needs to support an organization’s system for creating value (as Martin Jenkins explains in this blog post).

What is the value that you deliver to your customers and how are you delivering it? Does your organizational structure support this value delivery or does it work against it? Only you can answer that question for your organization.

Conclusion

Organizational structures are important for business to function and grow. Good organizational structures answer important questions, such as (i) what are you responsible for, (ii) who are you working with, and (iii) who do you report to and who reports to you.

Every organization is unique and there is no one size fits all. It’s important to know when additional structure needs to be added, simple concepts like the span of control and the two-pizza teams can help with that. When additional structure needs to be added, it can be healthy to revisit your current structure and evaluate what will be the best structure going forward. There are 3 main options that you can choose from, but ultimately you’ll have to find a structure that works best for your organization. As your organization grows, whatever structure is best for you may change.

FAQ